A 17th Century Sundial

An interesting object discovered while looking for something else

Matthew Macfadyen

The Story

This is the story of an interesting object discovered while looking for something else. Kirsty had thrown some weeds into a nettle patch, and realised that her wedding ring was missing. cue David Beaumont from Kineton with his metal detector. Two hours later we had a large area of nettles cut down, and had amassed several ring pulls, a tarnished pound coin, a few nails and a round muddy object. The wedding ring appeared a week later in the bottom of the shoe cupboard. The round object was a home made sundial, probably a bit over 300 years old.

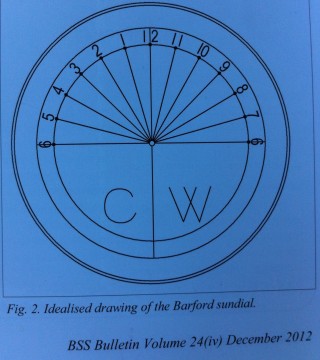

The dial is a disc of lead, about 1/8″ thick and 2″ diameter. One side is unmarked, the other is engraved with lines, circles and numbers. The photo shows the object, the drawing is a schematic diagram of the engravings.

We showed this to John Davis, of the British sundial society, who made the following observations:

- The numbers run anticlockwise, so the dial would have to be mounted on a vertical surface ( e.g. Wall or tree) to make the hours go forwards.

- There is a small hole in the centre of the dial, which would have received a fine pin, probably acting both to hold the sundial on the wall and as a gnomon to cast a shadow on the lines.

- The lines are spaced ( approximately) equally at 15 degree intervals, so the hours would not be of equal length

- The script used for the numbers dates the dial as later than 1500, and probably before 1700, though he notes that provincial practices may have lagged a few years behind the habits of the towns.

- The dial is inscribed with the letters C W. Presumably this would be either the maker or the owner. We note that the land was part of Barford Mill, and that the mill owner up to 1692 was one Charles Ward, though that is a long way from proving that is was his sundial.

- the rather imprecise marking, and the choice of lead (Cheap and easy to work) point to an amateur working with a sharp scriber and a pair of compasses, not to a professional clockmaker. Also, when the dial was in place on a wall the initials would be upside down which may have been a mistake.

Speculation

How might this sundial have been used? It will not have been much use for measuring how long anything took, but it would allow a particular time of day, say time for lunch or time to stop work, to be defined.

This type of wall mounted sundial is sometimes referred to as a ‘Mass dial’ because larger versions than this were often mounted on the south facing wall of a church to tell the parishioners when it was time to attend mass.

So we imagine Mr Charles Ward, mill owner, employing some workers on a day rate, and making ( or perhaps having his blacksmith make) this sundial. He then finds a suitable tree, cuts a blaze on the south side of it with an axe, and pins the sundial to the tree. The workers are allowed home when the shadow reaches 6. The sundial stays on the tree until the pin rusts, and is then lost.

Reference The British Sundial Society Bulletin, vol 24 (iv) December 2012

No Comments

Add a comment about this page